“Turkish Delight”—what is it? Most Americans have never tasted it or seen it, although they may have run into mention of it in The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe. This classic book for young readers—the first installment of C.S. Lewis’ Narnia series— features a boy named Edmund who colludes with a witch against his own family and the magical realm of Narnia, all because she promises him “Turkish Delight.” Journalist Jess Zimmerman asked a number of Americans how they had pictured this delicacy when they read the tale as kids. They told of imagining all kinds of sweets—a crunchy, peanut butter-infused chocolate bar; an enhanced pink Starburst; dense cotton candy flavored with cinnamon, ginger, cardamon, and honey; a near cousin of marzipan; and so on. Some had envisioned it not as a confection at all but as a favorite part of dinner’s main course—the perfect turkey stuffing, for instance. (Jess Zimmerman, “C.S. Lewis’s Greatest Fiction Was Convincing American Kids That They Would Like Turkish Delight,” Gastro Obscura, June 12, 2017.)

Turkish Delight is none of the above. It is a starch and sugar gel, typically infused with rose water, lemon, cinnamon, or other flavorings popular in Turkey. Sometimes it includes pistachios or walnuts. Served in small cubes that are commonly dusted with powdered sugar, it is a regular feature of daily life in Turkey, where it is known as lokum and is much-loved. These days, if you don’t have a local store carrying imported Turkish foods and you want to try lokum, a box of it can be purchased over the Internet easily enough.

Now imagine a different situation. Suppose you were eager to sample Turkish Delight but could not find it for sale in your area. Nor could it be ordered online. Suppose that, in fact, all around the globe, even in Turkey, Turkish Delight simply could not be obtained, although people everywhere talked about it and how wonderful it was. When you questioned some of them about this mystery food, they gave a variety of conflicting descriptions. You suspected they were lying to you, or perhaps were deluded. Perhaps they had been brainwashed when they were children, either by their parents or other authority figures. They sincerely believed they knew what Turkish Delight was, but they were simply repeating what they had been told. You wondered whether Turkish Delight existed at all. Was it just a powerful fable?

This is the quandary that many of us face when we hear about “God.” And we do, all the time. “God” is on everyone’s lips and at the center of our most immovable convictions and our most rancorous disputes. “Keep God in the schools,” “Keep God out of the public square,” “Same-sex marriage is against the law of God,” “God bless the whole world, no exceptions,” “Every human life is a sacred gift from God,” “God will punish those who put children in cages.” But what is God? What does this short, one-syllable English word mean? If we’re all God’s children—just whose children are we?

If you go by what people say, God is just about anything. Ask for a description of God from a cross section of believers (never mind agnostics and atheists) in the U.S. (never mind the rest of the globe). Ask an Orthodox Christian in Chicago, a Hindu in Atlanta, a reformed Jew in San Antonio, an evangelical Christian in Deerborn, a Shawnee animist in Oklahoma City, a Sunni Muslim in Pittsburgh, a Rastafarian in New York, a Mennonite in Portland, a Buddhist in New Orleans. You’ll find yourself in the position of a forensic artist trying to produce a composite image from descriptions offered by multiple witnesses—only each of these witnesses in fact saw a different individual. You can even confine your survey to individual members of a single confessional group—say, Hasidic Jews or Roman Catholics—and you’ll still get wildly contradictory responses. You’ll be left in a conceptual fog.

Christians make up a majority of religious Americans. Many of them might simply say, “God is Lord Jesus Christ.” To them, I should clarify that my question concerns, in Christian terms, “God the Father.” Jesus, according to Christian teaching, was conceived not through sexual intercourse like everyone else but by God’s impregnation of Mary. Who or what is the Being that created the embryo of Jesus in the uterus of a young woman named Mary who had never had relations with any man? Jesus is “the Son of God.” Of whom or what is Jesus the son?

The question “What is God?” is posed here for a specific purpose, namely, to identify some way of understanding God that is widely shared among Americans across political, religious, and cultural spectrums. That way, our disagreements, insofar as they involve “God” and what “God” requires of us, can at least be articulated with something approaching a shared vocabulary. We won’t be lacing our remarks and opinions, our speeches and slogans, with the word “God” when we all mean different things by it. No doubt we need a similar clarification about lots of terms for the same reason. “Socialism,” “patriotism,” “family values,” “liberal,” and “conservative” come to mind. But none of them has the power to confuse and distort our communication with each other quite like “God.”

Four Predicates

God is Almighty, God is Love, God is Eternal, God is Truth. Believers of almost all stripes concur that each of these predicates describes God’s essence. Maybe they can serve as the anchors of a shared understanding of God. Maybe. First we have to establish whether the four words—Almighty, Love, Eternal, and Truth—are themselves clear and comprehensible to the great mass of us, in more or less the same way.

“Almighty” God is all-powerful, able to do all things. A simple enough proposition. The pricklier issue is how we mortals should react to God’s magisterial power in leading our lives. Can we influence God’s will? Is it in God’s “tool kit” to change the course of things in response to our actions and appeals—for instance, to answer the prayers of homeowners living in the path of a wildfire and redirect the blaze elsewhere? Or to kill off an aggressive pancreatic tumor because the patient’s loved ones, a handful of human beings amid the billions of us, pray for a miracle? Does God’s nature include any impulse to honor our requests, if only on a spot basis? Or is the infinite power of God something different and beyond our comprehension, something that has nothing to do with the wishes that people, often in desperation, express in prayer? Should we heed the words of Ida Mae Gladding who, when faced with misfortune, always said “God don’t make no mistakes,” and leave it at that? Does prayer have any point at all? Does anything we do make any difference to God? You can be sure that people will have sharply conflicting views about these questions. Inevitably, they’ll be equally at odds about the proper understanding of “Almighty.“ “Almighty,” it turns out, is as much a black box as“God.”

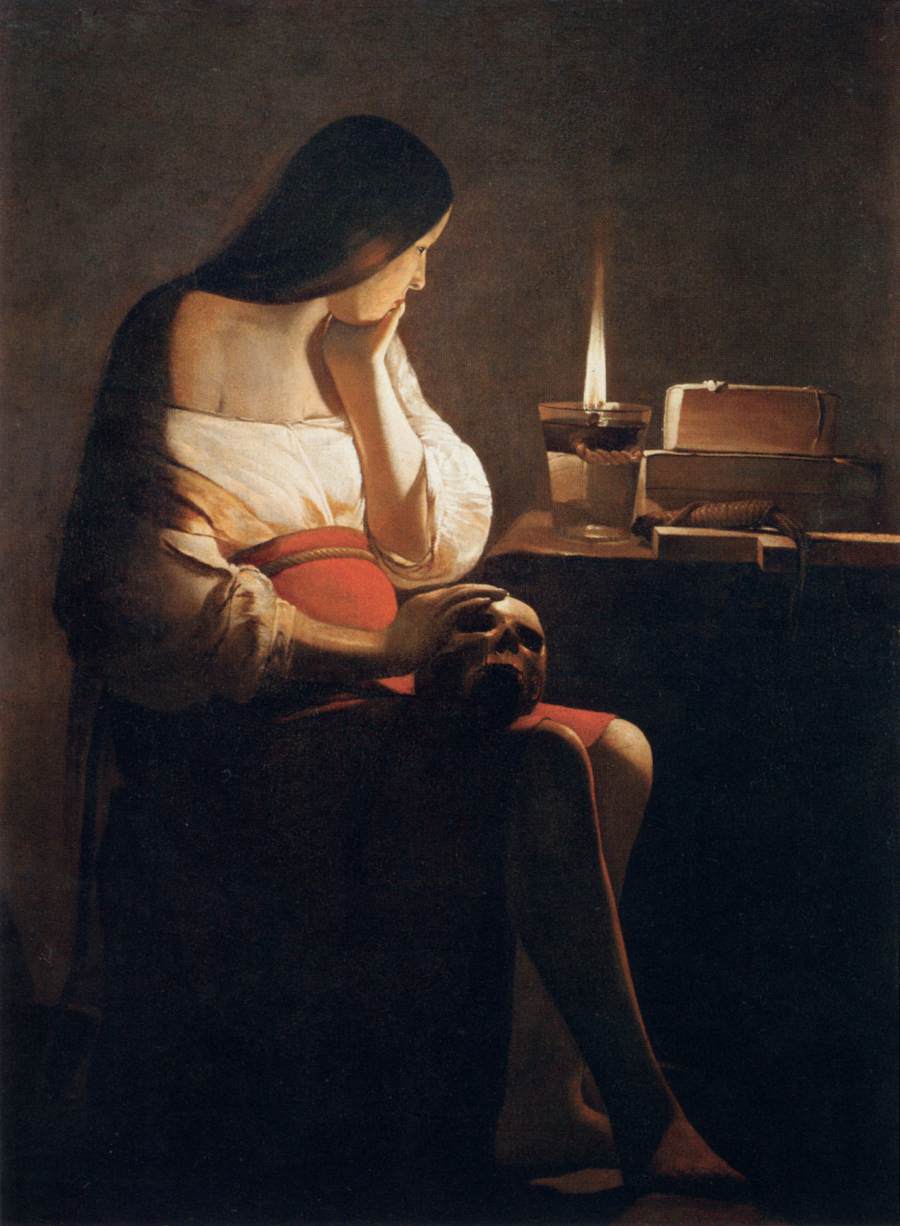

“Love” is something we can all relate to more easily than “Almighty.” That’s the problem with Love. Love has great immediacy for us in all its forms, which range from the most selfless to the most pleasure-crazy and animal. You can try to slice and dice the concept Love, to isolate the part of it that applies to God. This is sometimes done by leaning on Ancient Greek, specifically two Greek words for Love—Eros (Ερος) and Agape (Αγαπη). From the pulpit, members of the clergy like to go on about Agape and to contrast it with the less reputable Eros, even though most of them have, at best, a superficial knowledge of Greek and no inkling of the rich complexity of love terminology in the ancient texts. That’s a subject best left to expert philologists. The truth is that, no matter what language or culture you pick, ancient or modern, Love is as tangled a concept as it is dizzying an experience. About that, you don’t need to consult experts, you can just ask anyone who has been in love. “Love,” the ultimate labyrinth, isn’t a promising path to consensus about God.

“Eternal” as applied to God’s realm (“Heaven,” ”Life Everlasting”) has been on the receiving end of a hail of hilarity in literature and elsewhere. For my money, Mark Twain takes the prize with his arch observations on the subject, like this one: “Most people can’t bear to sit in church for an hour on Sundays. How are they supposed to live somewhere very similar to it for eternity?” If we’re honest with ourselves, an afterlife that goes on and on, appending eons like the digits after the decimal point in π, is a hard sell to our intelligence. Even if we try to imagine it as carefree, struggle-free, and exertion-free, more so even than the Big Rock Candy Mountain, the afterlife prospect isn’t so much joyous as plain weird. And not just in modern positivist terms. Science aside, a paradise that awaits you after you die has no place in any kind of consideration of Eternity, including theological and metaphysical ones. Concerning Eternity, the one thing we can be sure of is that it transcends time and temporal concepts like “before” and “after.” The right place for the afterlife is where we usually find it—in cartoons and the wisecracks of honest people like Mark Twain. But as long as countless clergy and lay people accept afterlife stories (or at least give them lip service) as reality, “Eternal” would be another sinkhole as the foundation for a common understanding of God.

“Truth” we innately grasp. It is built into us, and for good reason. It enables us to make judgments about what is and is not real, a critical capability for our well-being and our very survival. Without it, we could learn nothing—not even that a rose thorn is sharp or ice slippery or fire hot. Truth is not a difficult idea or construct. A child quizzed by her parents about two cannolis missing from the fridge knows she is fibbing when she denies having made a snack of them. She may not be as skilled at rationalizing her deceit as adults—say, scientists who fudge evidence to suit an experiment’s desired outcome—but even at her young age she has the same faculty for distinguishing truth from untruth as they do. As long as we’re compos mentis, we have that faculty as human beings. What about ”to err is human”? Of course to err is human. We reach erroneous conclusions all the time about specific matters in the world around us—we genuinely accept something as true when it isn’t—but such misjudgments are not due to a deficient sense of truth. They happen for other reasons, usually because we’ve relied on incomplete or misleading information or because we’ve allowed our partisan emotions to take charge. They are like a sour note hit by Itzhak Perlman. His execution of the note may have failed, but his ear—his perfect pitch—isn’t to blame. We form mistaken opinions right and left, but when it comes to truth itself, we have pitch as pure as Perlman’s.

“God is Truth.” We should all be able to agree on this. Even atheists. Atheists have the same inborn sense of truth as everyone else, so if we ask them to think “Truth” when someone uses the term “God,” why should they object? The equation God = Truth, or Truth = God, doesn’t impose religion on anyone. Religion is what worshippers practice as they enact rituals and carry on received traditions. It is the recitation of the rosary, the crouch to pray when the muezzin cries out, the blowing of the shofar at Yom Kippur, the singing of “On Jordan’s Bank” at a Wednesday night church supper. It is, in various faith traditions, fasts and special dietary rules, the recognition of certain persons or texts of authority, the delineation of separate (and grievously unequal) roles and requirements for men and women, the obligation to gather as a congregation at fixed times. None of this is required to accept “God” as a synonym for Truth.

We pursue Truth every day, in ways ordinary and extraordinary, whether we’re stepping on the scales at the gym, testing soil for pollutants, reading a newspaper or Faulkner or Lucretius, tagging salmon, refereeing a football game, measuring the bones of early hominids, learning Spanish irregular verbs, or performing research towards a Parkinson’s cure. If only we would come to see all such activities as communing with the divine. If only we would make the search for Truth, no matter where it takes us, the holiest of sacraments. God is Truth.

George Angell, Baltimore, December 2019